By Kerstin Arnold, Cory Nimer, and Mary Samouelian

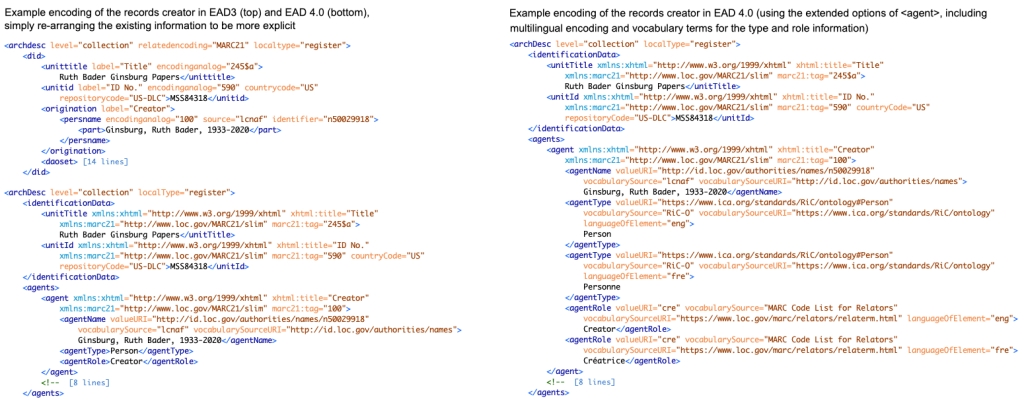

In our previous blog posts, we first shared an insider’s look into the revision process of the Encoded Archival Description (EAD). Next, we talked about the importance of standards alignment with a focus on the work that has been done to align EAD 4.0 with its sibling standard, Encoded Archival Context – Corporate Bodies, Persons, and Families (EAC-CPF). In this post, we will now dive deeper into one of the more conceptual changes specific to EAD: relationship information.

A Matter of Relations

When EAD3 was published in 2015, it introduced the new element <relations>, which it adopted from EAC-CPF. This element was meant to encode details about the relationship between the materials being described and other entities, that is, persons or organizations in their roles as record creators, and also other archival or bibliographic resources. Beyond naming those entities, <relations> also allowed for providing information about the temporal and spatial dimensions of their relationships with the archival records. With this, it expanded on the functionality of existing elements, such as <origination>, which focused solely on encoding the name(s) of the records creator(s), or <relatedmaterial>, which was mainly set up to include longer narrative text.

Some in the archival community as well as in the then-Technical Subcommittee on Encoded Archival Description (TS-EAD) believed using <relations> would be essential to supporting Linked Open Data applications. On the other hand, others felt that it duplicated functionality present in existing elements. This led to <relations> being included in EAD3 as an “experimental” element, and it was not guaranteed that it would be included in the next version of EAD.

An Integrative Approach

As <relations> was not included permanently in the last version of EAD, we have reviewed the pros and cons of this element over the course of this revision. Through several rounds of conversations we looked at different options to encode relationship information from various perspectives. The basis for our considerations were the further developments in the realm of Linked Open Data since the publication of EAD3, as well as the increased uptake of conceptual and reference models by the cultural heritage sector. One of these models is the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC-CRM), which originates from the museum sector, but is used by other types of cultural heritage institutions as well. We also looked at similar models used in the library domain such as the IFLA Library Reference Model (LRM) and BIBFRAME. And — most prominently and most closely — we followed the development of the Records in Contexts Conceptual Model (RiC-CM) as led by the ICA Expert Group on Archival Description (EGAD).

Building on those models and standards, EAD 4.0 suggests two major changes to describing related entities and their relationships with the archival materials themselves:

- related entities and their relationships now have a dedicated place within the structure of an EAD XML document rather than being part of a bigger group of either identifying or narrative elements;

- <relations> can be included as part of those descriptions rather than duplicating this information in a separate section of the EAD XML document

The Who, Why and Where

The first grouping of relationship information, or related entities, includes agents, functions, and places and answers the questions of who, why, and where. Who created the materials? Who used them? Who arranged them? Who is mentioned in them or has had an impact on their contents in any other way? Why were the materials created? Why were they considered of historical importance and to be kept? Why are they organized and grouped in the way they are? Where were the materials created? Where were or are they held and made accessible? Which locations play a role in understanding their contexts?

To encode all of this information, EAD 4.0 will include the grouping elements <agents>, <functions>, and <places>. Each of these elements holds one or more of their singular forms, i.e., <agent>, <function>, and <place>. With these it will be possible:

- to name the related entity (e.g., “Supreme Court of the United States” or “Ruth Bader Ginsburg” or “Judicial power” or “Washington, District of Columbia”);

- to specify their type (e.g., if an <agent> is a “person” or an “organization” or if the <place> Washington is the “capital of a political entity” (as in Washington, District of Columbia) or a “first-order administrative division” (as in the State of Washington));

- and to provide information about their role in relation to the materials being described (e.g., if a person is the “creator” of the materials or a “contributor” or if they are the “director” or the “cinematographer” of audiovisual material or the “defendant” or the “plaintiff” in court records).

Furthermore, the relationship between the entity and the materials described can be categorized more generally and, as was the case before, the temporal and spatial dimensions of the relationship can be added.

The What

The second grouping of relationship information pertains to the archival materials themselves and includes elements such as <formsAvailable>, <relatedMaterial>, <separatedMaterial>, <otherFindAid>, and <publicationNote>. With these elements, it is possible to name and describe:

- any analog or digital copies of the materials, e.g., paper copies, microfiches, digitized representations such as JPEG or TIFF image files, as well as originals held by someone else if the descriptive unit itself consists of copies;

- any archival records which relate to the materials by subject matter, but are, e.g., held by another repository;

- any archival records which relate to the materials by provenance, but have been physically removed, e.g., due to storage or preservation requirements;

- any other finding aids or guides to the materials;

- and any (published) works based on the use or analysis of the materials.

Building on these elements’ equivalents in EAD3, the new version of EAD still enables the description of these related entities using continuous texts with repeated paragraphs, lists, etc. In addition, EAD 4.0 allows for <relations> to be used within these elements to enhance such descriptions with a more explicit encoding of the relationships between the archival materials described and any related materials or forms.

An Extensible Concept

It is important to note that, while EAD 4.0 suggests a new way of encoding information about related entities and their relationships with the materials being described, it does not necessarily or always require additional information compared to existing practices of archival description. It does, however, allow people to expand upon existing information.

In some cases, it might still be sufficient to focus on simply naming related entities, such as when the main usage context is a simple full-text search across the archival descriptions of a single institution. In other cases, it might be helpful for the people creating and managing the descriptions as well as the users of the descriptions to have more information available about those entities and their relationships with the materials described. Such further information might be added by including references to external vocabularies that already provide the wanted details and support the international interoperability of archival descriptions. Or such information is enabled by using the encoding options for types, roles, and temporal and spatial dimensions that EAD 4.0 offers to support more sophisticated access, for example based on a distinction of various roles or with a date- or map-based user interface.

What Can I Do to Participate?

The first draft of EAD 4.0 was published on 19 April and will be kept open for community feedback until the end of July. To make sure that the updated version of EAD fits our community’s requirements and that the benefits of a new version of EAD outweigh the challenges of transitioning from one version to another, the members of the EAD sub-team want to hear your comments, questions, suggestions, and concerns about EAD 4.0. You can provide feedback via GitHub, our web form, or the TS-EAS email, ts-eas@archivists.org. We are not doing this work alone!

Furthermore, we are happy to invite you to one of our remaining informal drop-in sessions to discuss the main features of the new version:

- Tuesday, 18 June, 6am UTC (open for registration)

- Tuesday, 9 July, 4pm UTC (open for registration)

The recording of our previous sessions can be found on SAA’s YouTube channel.

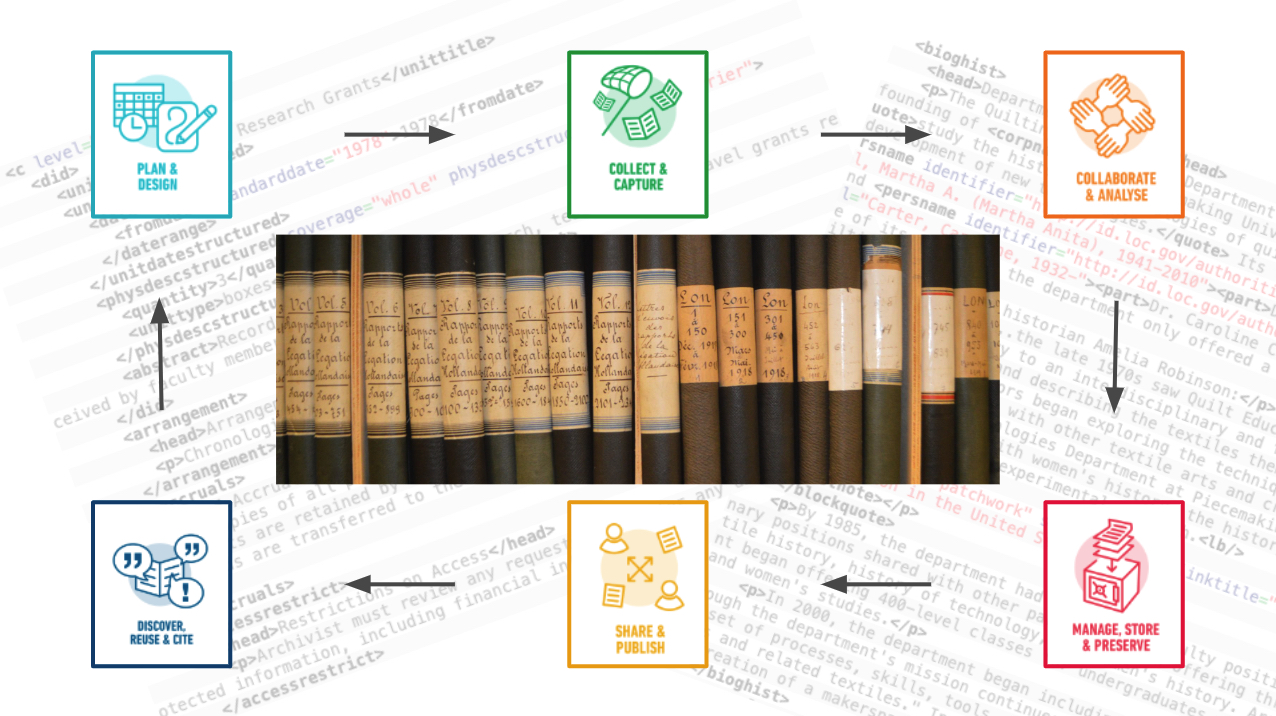

Top image citation: All about Archives – The Major Revision of the Encoded Archival Description standard, 2021-2024. [sources: (1) Public archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Geneva, Switzerland. By Roman Deckert. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CICR-ICRC-PublicArchives_WWI-files_RomanDeckert09062020.jpg; (2) The Research Data Management (RDM) lifecycle at the University of Cape Town (UCT). 1 December 2018. Design by Gaelen Pinnock. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UCT_RDM_lifecycle_%28all_icons%29.svg; (3) Encoding examples. EADiva Tag Library by Ruth Kitchin Tillman. https://eadiva.com/dsc/ and https://eadiva.com/archdesc/; (1) and (2) CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0), (3) CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)]

Kerstin Arnold is the Chief Operating Officer for Archives Portal Europe, an aggregator gathering more than 650,000 archival collection descriptions from over 1,200 institutions in 30+ European countries. She leads the EAD sub-team of the Technical Subcommittee on Encoded Archival Standards (TS-EAS).

Mary Samouelian is the Manager, Archival Processing for Baker Library Special Collections and Archives at Harvard Business School. She is the co-chair of TS-EAS and a member of the EAD and Outreach sub-teams.

Cory Nimer is the University Archivist at Brigham Young University. He leads the Outreach sub-team of TS-EAS.