By Alexandra (Lexy) deGraffenreid

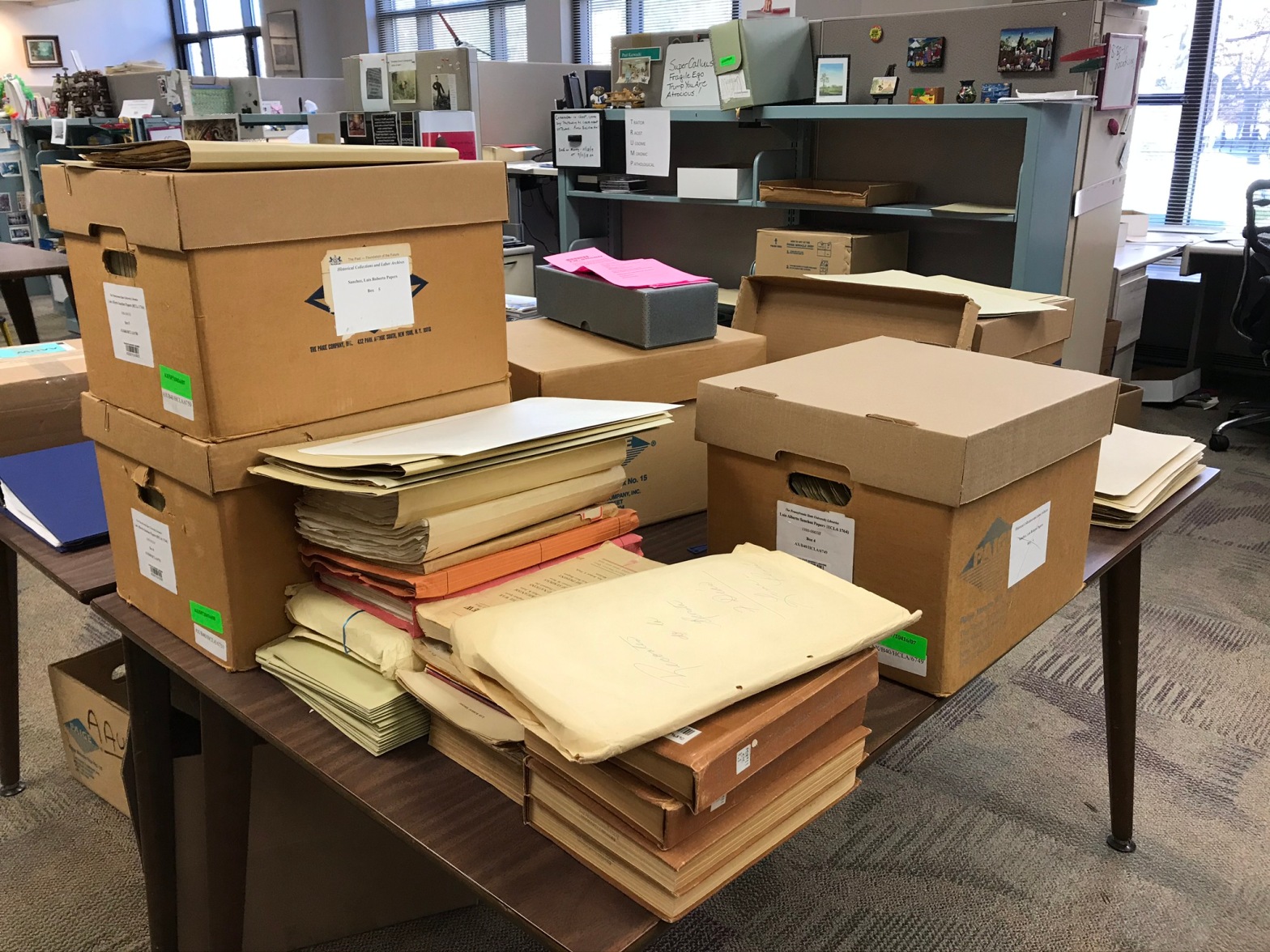

In 2019, Pennsylvania State University’s Eberly Family Special Collections Library reprocessed the Luis Alberto Sánchez papers. This collection forced us to confront and repair legacy archival practices in order to promote its accessibility and use through bilingual description and notes describing the papers’ curatorial history. This collection’s layered and troubled history, extensive curatorial mediation, and lack of transparency about archival interventions required the processing archivist to think critically about the ways previous archivists’ decisions impacted the collection and the ability of researchers to access and use the materials.

Luis Alberto Sánchez was an author, politician, and leader within Peru’s first political party, Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA). Peruvian Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre founded APRA in 1924 while in exile in Mexico City, as an anti-imperialist party looking to politically unify Latin America.[1] Dr. Sánchez, a published author, subdirector of the Biblioteca Nacional del Peru and President of the Asociación Nacional de Periodistas, joined the party in 1931. Dr. Sánchez was a leader within the party, including serving as the director of La Tribuna, the party’s newspaper. He ultimately became a Peruvian Senator and later Peru’s Vice President in the 1980s.[2] During this time Peru’s political climate was turbulent and violent. Peruvians experienced coups, dictatorships, political repression, and political violence. As a leftist populist political party, APRA and its members were frequently both the target and the perpetuators of violence. As a result of this political repression and violence, Dr. Sánchez endured multiple periods of exile.

Dr. Sánchez’ papers reflect this history and demonstrate the intersection of political and literary networks in mid-20th century Latin America. His correspondents include political leaders Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, José Carlos Mariátegui, Fernando Belaúnde Terry, and Rómulo Betancourt, as well as literary figures Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, and César Vallejo. His papers document not only Peru’s political struggles, but also political upheaval in other Latin American countries such as Cuba, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic. The papers include accounts of exile, political violence, and suicide.

In 1969, bookdealer S. R. Shapiro approached Dr. Sánchez about selling his library and papers to Pennsylvania State University. In the signed agreement, Dr. Sánchez agreed to sell his papers, and approximately 14,000 volumes, to be transferred to the library in three shipments between 1969 and 1976.[3] Aligned with the content of the collection, the initial 1969 shipment of books was delayed in part due to the military dictatorship in power in Peru at the time.[4] While the library was transferred in three shipments, the bulk of the papers arrived in an unknown number of shipments throughout the 1970s (with small later accruals until 1991).

Throughout his relationship with Penn State, Dr. Sánchez was careful and deliberate in curating his papers. Due to the political situation, much of the APRA-related correspondence is written under pseudonyms and includes coded language. Dr. Sánchez carefully identified the correspondent in each letter and frequently summarized a letter’s contents for clarity. He also carefully arranged his papers into three series prior to shipment: literary, political, and personal.[5] Additionally, he hired two women, Frida Parnes de Sardón and Professor Marlene Polo (a Peruvian academic), to select, arrange, and classify papers for transportation to Penn State.[6] Decades of correspondence, currently part of the collection, document the long relationship between Dr. Sánchez and Penn State librarians as well as the careful curation of his papers.

Despite Dr. Sánchez’ sustained efforts, his original arrangement was disregarded. Initially processed in the 1970s, the papers look to have been re-processed over time as new materials were added to the collection through the early 1990s. Archivists loosely grouped materials into correspondence, manuscripts, and assorted other materials. The correspondence was interfiled together alphabetically by correspondent, erasing all delineation between the literary, personal, and political materials. In addition, correspondence belonging to his friend Alfredo González Prada, and collected by Dr. Sánchez, was interfiled into the overall correspondence. The finding aid contained no arrangement, no dates of materials, minimal notes, and the description was entirely in English (despite the majority of the collection being in Spanish). These factors disrupted Dr. Sánchez’ original intent and made the collection difficult to access and navigate.

Although no processing notes survive from the initial processing, evidence of the papers’ curation also exist throughout the materials. Archivists interfiled the correspondence between Penn State and Dr. Sánchez into the collection. Collection file information and curators’ notes are present throughout the collection, including annotations on folders and post-it notes placed within folders about important topics and persons represented within letters and manuscripts. Correspondence received after the publication of an annotated calendar of the correspondence in 1982 includes a sheet informing researchers that Penn State received this letter after publication and provides Dr. Sánchez’ summary of its contents. Separation sheets also demonstrate how materials were removed from their original locations and interfiled into other parts of the collection. While these traces of curatorial work demonstrate the curators’ well-intentioned attempts to make the collection more accessible, they also demonstrate the layers of archival intervention imposed on the papers. Where these mediations might otherwise be invisible to users, within the Luis Alberto Sánchez papers they are pervasive and fully visible to researchers. They clearly demonstrate how the work of previous archivists indelibly impacted these papers and is inseparable from the collection as it currently exists.

The idea to revisit this collection began with librarian José Guerrero. He researched the collections’ complex custodial and curatorial history and identified Dr. Sánchez’ remaining library at Penn State. He advocated for reprocessing the papers due to the current state of the collection, its limited accessibility, and its historical importance. Guerrero left Penn State before work could begin, but in 2019 after reviewing Guerrero’s work, it was clear that the papers required reparative work. We were highly concerned about its inaccessibility to Spanish-speaking researchers, due to the English-only description and its displacement from Peruvian researchers due to the geographic and logistical difficulties associated with its location in central Pennsylvania.

To remediate previous archival interventions and the papers’ inaccessibility, reprocessing this collection had four goals: 1) facilitate Spanish-speaking researchers through bilingual description, 2) redescribe the collection in a way that would help curatorial staff better advocate for digitization (and thus access for international researchers), 3) recover Dr. Sánchez’ voice within the collection, and 4) be transparent about the layers of custodial and curatorial history present within the collection.

The hardest of these to address was the third, as Dr. Sánchez’ original order was impossible to recover as we could not conclusively know how all the materials were previously classified. We decided to retain Sánchez’ correspondence with Penn State librarians within the collection to demonstrate his own careful curation and interpretation of materials. This correspondence was also previously available to researchers and demonstrated the decades-long relationship and curatorial history. To highlight its inclusion, we created a series for Pennsylvania State University and used the Scope and Content note to describe this correspondence, the existence of other material collected by Penn State about Dr. Sánchez, and the reason for its inclusion.

To address the other archival interventions, we focused on the Custodial History and Processing Information notes to try and be as transparent as possible about the papers’ history. Using the Custodial History note, we outlined an abbreviated history of the collection, including that the papers survived periods of exile and that parts of this custodial history were unknown. In the Processing Information note, we provided a brief overview of how materials had been arranged and re-arranged by Frida Parnes de Sardón and Penn State archivists prior to 2019 as well as detailing all activities undertaken to reprocess the papers. In creating such detailed notes, we hope this sheds light on how previous archival interventions have impacted researchers’ ability to use and understand the materials.

Despite the extensive reprocessing and the new bilingual archival description, this reparative work is incomplete. There are plans to digitize portions of the collection, but this has not started due to the pandemic and other digitization priorities. While the collection now has finding aids in both English and Spanish, this does not fully repair the relationship with the Peruvian community due to its geographic dislocation. However, reprocessing the Sánchez papers to highlight archivists’ mediation within the materials and facilitate bilingual access was the first crucial step to ensure that these invaluable records of political upheaval, violence, and transnational networks are accessible to Peruvian and other Latin American researchers.

[1] Cozart, Dan, “The Rise of APRA in Peru: Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre and Inter-American Intellectual Connections, 1918–1935,” The Latin Americanist 58, no. 1 (March 2014): pp. 77, 81.

[2] Polo Miranda, Marlene, “Cronología: Vida y obra de Luis Alberto Sánchez,” unpublished manuscript, circa 1989, Box 14, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University.

[3] Memorandum from Luis Alberto Sánchez to S.R. Shapiro, 17 March 1969, Box 13, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University; Memorandum adicional, 25 March 1969, Box 13, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University.

[4] Correspondence from S.R. Shapiro to Murray S. Martin, 25 October 1969, Box 13, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University.

[5] Correspondence from Luis Alberto Sánchez to Murray S. Martin, 22 October 1973, Box 13, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University.

[6] Correspondence from Luis Alberto Sánchez to Murray S. Martin, 4 August 1969, Box 13, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University; Correspondence from Luis Alberto Sánchez to Murray Martin, 26 April 1977, Box 13, Luis Alberto Sánchez papers, 01764, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University.

Alexandra (Lexy) deGraffenreid is the Interim Co-Head of Collection Services and Processing Archivist at Pennsylvania State University. She graduated from the University of Michigan with her MSI specializing in archives and records management in 2015 and previously worked as a Staff Archivist for History Factory.