By Katy Sternberger

Archivists generally try to avoid accepting collections on deposit, especially because it is hard to justify investing resources in a collection that actually belongs to another entity. Nevertheless, sometimes circumstances dictate taking in such material. This was the case at the Portsmouth Athenaeum in 1988 when it accepted a collection on deposit from a neighboring institution that sought secure, climate-controlled storage. A finding aid was created in 1991, but it had not been updated since then for the obvious reason that the collection did not belong to the Athenaeum. Following a research request in August 2020, however, it was clear that a series of letters in the collection needed staff attention. This article discusses how I balanced providing increased access through description while not overly investing in material still in the legal custody of another institution.

Incorporated in 1817 and one of fewer than twenty membership libraries remaining in the United States, the Athenaeum includes a research library and archives in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. As a research librarian there, I not only provide reference services but also conduct in-depth research to facilitate access to our collections.

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic in the summer of 2020, when researchers were not able to travel, the Athenaeum received a request for digital access to letters exchanged between abolitionists Angelina and Sarah Grimké and Portsmouth peace activist William Ladd. These letters are part of a larger collection, the William Ladd papers (MS017). While Angelina and Sarah were the primary correspondents, Ladd also communicated with Anna Grimké Frost and Thomas Grimké, whose untimely death in 1833 sparked a friendship between Ladd and the Grimké sisters. In total, there are forty-six letters dating from 1828 to 1839, arranged chronologically across four folders.

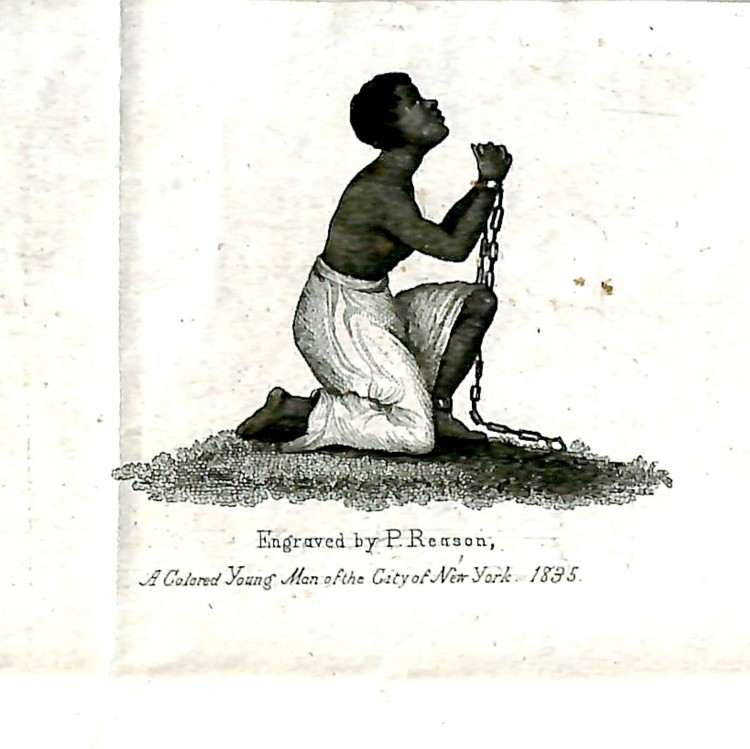

Abolitionists Angelina and Sarah Grimké connected with Portsmouth peace activist William Ladd after the untimely death of their brother, Thomas Grimké. Over the course of 1833–1839, a pivotal time in the sisters’ activism, they developed a strong friendship with Ladd, as indicated in a May 1, 1838, wedding invitation from Angelina. The letterhead includes an 1835 engraving by Patrick Reason, who was “A Colored Young Man of the City of New York.” The image, often seen with the slogan “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” features an enslaved woman in chains kneeling. Reason designed the letterhead for the American Anti-Slavery Society after a 1787 image created by potter and abolitionist Josiah Wedgwood. Courtesy of the Portsmouth Athenaeum, William Ladd Papers (MS017), on deposit from the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of New Hampshire.

Previously underutilized by Grimké scholars, this correspondence covers the 1830s, a period during which the sisters were particularly active in speaking and writing about abolition and women’s rights. The letters are rich with details about the sisters’ publications and struggles with their Quaker faith. However, a lack of context and numerous errors in the original finding aid made it difficult to use the material, especially remotely. The researcher could not identify what they needed without the intercession of Athenaeum staff who could physically look at the material.

Additionally, the Grimké correspondence posed particular challenges because the William Ladd papers are on deposit by the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of New Hampshire. The society owns the Moffatt-Ladd House & Garden in Portsmouth and previously stored its archives in the attic of the historic house museum. Since the storage conditions were obviously not in the best interest of the collection or the researchers looking to use it, the society deposited the Ladd papers at the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

The Athenaeum’s deposit agreement allows us to provide access to the materials, including the ability to send digital images to remote researchers. But before I could even provide access to the Grimké sisters’ letters, I needed to review and make necessary corrections to their existing description. Because the Grimké letters were only on deposit, I could not rationalize spending too much time describing them. As I started working with the material, though, I quickly realized that I had to start from scratch.

The original finding aid for the entirety of the William Ladd papers listed each of the Grimké letters with the date, the sender’s initials, the recipient’s initials, and occasionally a very short description of the letter’s content. And yet, I could not match up the finding aid’s description with the letters in my hand. Many of the dates were typographical errors, names were incorrect, and the brief descriptors were so generic that they were unhelpful. I became concerned that some letters had gone missing since the gaps between the physical item and the surrogate record were so great. So, I began by recording the correct date of each letter and updating the finding aid.

Although I revised the finding aid and shared it with the researcher, simply correcting the dates didn’t increase the accessibility of the letters, nor did it address my concerns about possibly missing letters. To help make the Grimké correspondence more discoverable, I wrote item-level description for each letter. While archivists normally don’t describe collections at the item level, I wanted to uniquely identify each letter with a brief summary of its content, laden with subject headings. While looking closely at each letter and writing the item-level description, I also found that I needed to make slight revisions to the arrangement of the letters; due to incorrect dates in the original finding aid, the letters were not in chronological order as intended.

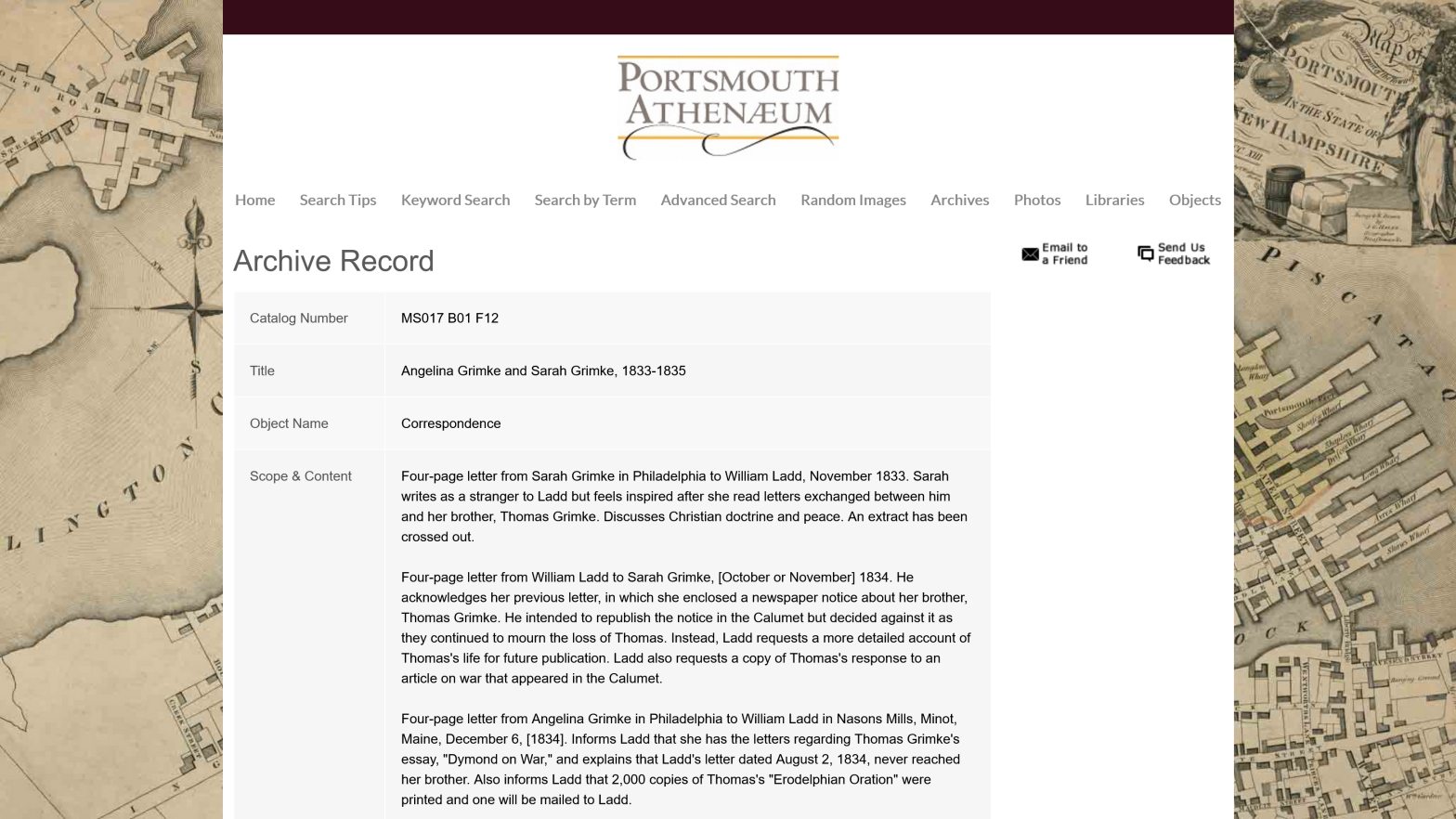

A screenshot of the Athenaeum’s PastPerfect catalog shows an item-level description for the first set of letters (folder 12 of the William Ladd papers), dated 1833–1835, from Angelina and Sarah Grimké to William Ladd. United around the cause of peace, the Grimké sisters established a relationship with Ladd when they began exchanging the publications of the late Thomas Grimké.

As it turned out, the correspondents also made a few mistakes that added to the confusion. For instance, a letter from Sarah Grimké to William Ladd is clearly dated August 7, 1836, during a respite in Shrewsbury, New Jersey. However, the researcher informed me that Sarah did not arrive in Shrewsbury until the end of August. As evidenced by the content of the rest of the letter, it must have been written instead on September 7, 1836. It took considerable time, but with the researcher’s expertise as a Grimké scholar and mine as an archivist, we sorted out all of the description errors.

Finally, in order to add the new description to the catalog, I created folder-level catalog records. This helped to ensure that the Grimké correspondence, which could be of great value to future researchers, was not buried within the rest of the finding aid for the William Ladd papers. Plus, I no longer had to work within the confines of the legacy finding aid. As access points, I listed subjects and geographic locations and added authority records for all persons. I finished the majority of the work in November 2020, and I continued refining the new catalog records through March 2021.

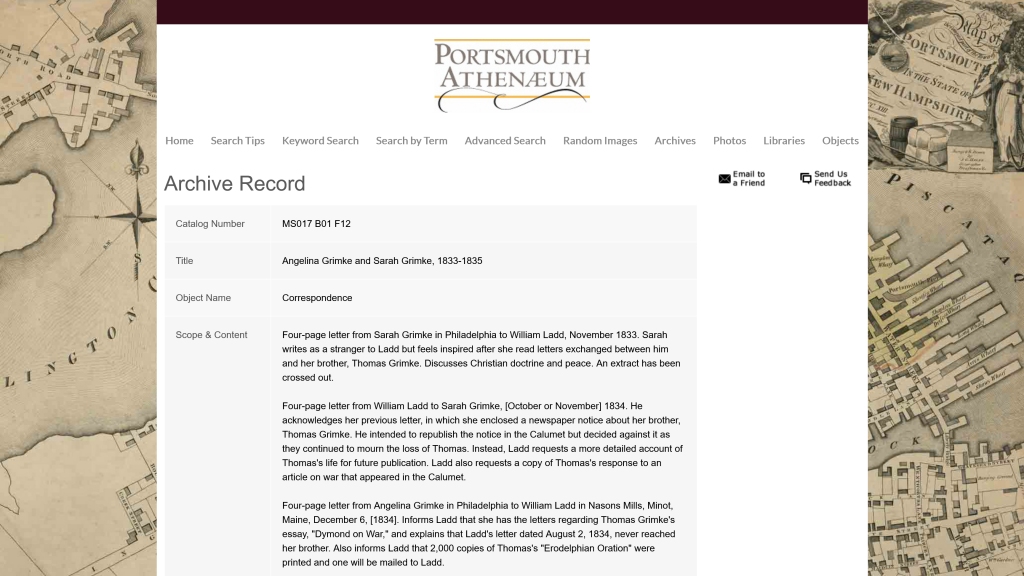

Another screenshot of the Athenaeum’s PastPerfect catalog shows some of the subject headings for the first set of Grimké letters (folder 12 of the William Ladd papers). The folder-level catalog records are linked to one another and to the collection-level catalog record via “Show Related Records…” Not shown, authority records for all persons mentioned in the letters are similarly linked.

Description is an iterative process. It can—and should—be revisited over time. I would, of course, like to do more in the future to increase discoverability of the Grimké correspondence, such as filling out the catalog records with more contextual information. I was under a time constraint because the researcher I was working with needed to have the correct information. In addition, I found that I was somewhat limited by our cataloging software, PastPerfect. As an example, our version of PastPerfect does not represent hierarchical relationships well. I could only link the collection-level catalog record as a “related record” to my folder-level catalog records. More broadly speaking, the Athenaeum should periodically reevaluate deposit agreements in order to mitigate the challenges associated with caring for loaned material.

Even still, the work I completed has already vastly improved access to these letters of value to the history of the abolition movement and women’s activism. Not only did I determine that no letters had gone missing, the researcher was able to pinpoint the letters they needed to see digitized. This experience also enabled me to start a conversation with my colleagues about how to better manage collections on deposit, and I rewrote our deposit agreement in December 2021 to more precisely describe the relationship between the depositing entity and the Athenaeum. Description isn’t perfect, but it is a continual process of increasing accessibility.

Katy Sternberger is an archivist, editor, and writer. She currently works as a research librarian at the Portsmouth Athenaeum in New Hampshire. Additionally, she serves on the Society of American Archivists Dictionary Working Group and the Lone Arrangers Section Steering Committee. In 2020, she became a Certified Archivist and completed the Digital Archives Specialist certificate from SAA.