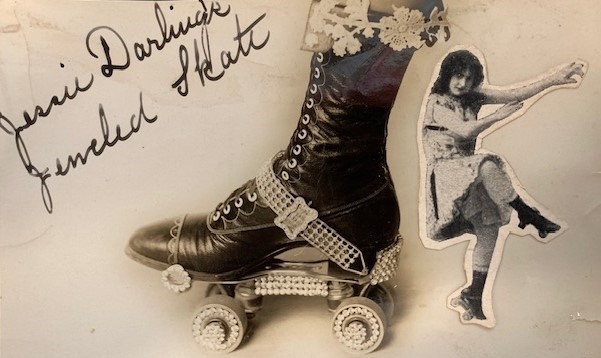

Image above: Jessie Darling’s jeweled skate, circa 1910-1915 (Houghton Library, MS Thr 2149)

By Melanie Wisner

The creation of an accession record marks the debut of a collection under new ownership. I dedicate this post to practitioners of the craft of accession-level titling of collections. “Craft” because I think it’s trickier than DACS 2.3 leads one to believe (“…simply names the unit as succinctly as possible”) and because it brightly spotlights archival judgment, the priceless talent as difficult as stardust to pin down.

I am grateful to Rachel Poppen for her thoughtful blog entry on just this point from the perspective of a relative newcomer (in contrast to mine from across many years). Despite Audra Eagle Yun’s Archival Accessioning and the work of the National Best Practices for Archival Accessioning Working Group, I think the business of titling accessions will remain a generous dollop of art topping a small biscuit of science.

I must say first that accession titles at my repository, the Houghton Library at Harvard, may not always achieve the excellence we aspire to, but we try our best. Second, I’m talking here about titles devised for new collections, and new collections of a particular size. Single item manuscripts and accruals are different animals, and large collections are usually “papers,” “records,” or “collection” (the bigger, the simpler). I mean collections that are small to medium and uneven in content and content types. Take the following two real-life examples, the first a collection from a vaudeville duo:

- a small stack of manuscript songs,

- numerous printed programs,

- a few photographs of a child in costume,

- a few letters,

- one sequined dress,

- and three wooden juggling clubs

This collection is materially diverse and yet focused enough that wrapping it up as “Tenny & Allen vaudeville act collection” seemed acceptable. But take this collection from an early female astronomer:

- two bound volumes of her astronomy offprints,

- and three glass-plate astronomical photographs

What to call it? It became “Antonia Maury collection of publications and astronomical photographs.” It’s sometimes simplest to just name the stuff, particularly if something is unusual. Though she owned the collection and wrote the content of the offprints, we think Maury did not create the photographs, so leaving the issue of creatorship a bit vague is OK with me. The word “astronomical” establishes the context. The lesson here is that the smaller the collection, the more precise the title may need to be.

We practice accessioning as processing at Houghton, and accession record titles become resource record (finding aid) titles. Accessioning is usually our first reveal of a collection to the outside world—and it may be the last word if the collection is not slated for further processing. Accession-level description needs to be able to stand the test of time. (We do have a robust practice of capturing and using feedback about finding aids, though, so nothing is truly writ in stone.) Words sometimes associated with accessioning as processing include “minimal” and “baseline”; these, in my view, mischaracterize the descriptive aims of accessioning. The magic is to concoct the truest representation of a collection in as few words as necessary.

The title is important because it is the highest-level surrogate for a collection, the boiled-down essence of the accession. The repository’s biases, as codified in repository documentation, habit, and lore, do suggest points of emphasis and even specific language. Having local guidelines and documented curatorial directions, as we do, helps, but they are only a jumping-off point. A title example:

Records related to legal actions involving Doris Day, the New Yorker, John Updike, and Jerome B. Rosenthal

We would normally try to specify the nature of the legal issues involved, but this situation from the 1980s is so tangled that no one or two words capture the whole. Houghton holds the papers of writer John Updike, so we are inclined to note his presence; the other equivalent participants should then also appear. The documents are not legal records; the individuals named are chiefly subjects but occasionally creators. Hence the words “related” and “involving.” The accessioner builds a set of descriptors to cover all shades of gray.

Accessioning is also, in my setting, usually the first exposure of the collection to an archivist. Donors, dealers, shippers, mailroom workers, and others have seen and handled the collection, but at accessioning we view it through the lens of the archival lifecycle—rather than as static merchandise. During the collection’s pre-custodial life, various parties have already described it, to be sure. This description may already be public, as in the case of pre-sale advertising written by dealers; but the advertising is meant to influence potential buyers (in our case, curators).

Collection titles may unintentionally misidentify, misspell, or miss entirely creators, material types, or collection dates. The title may skew toward a character or context we don’t want to lionize. A little research and thought can usually clarify where the given title and description are misguided—or it can reveal further factual murkiness like the attribution of creators, places, subjects, or dates for which there seem to be no basis. Over time, an instinct develops about what to look for, what to keep, and what to lose.

Creating titles also requires, among other little talents, some mastery of collective nouns and genre terms found in the Library of Congress Authorities and the Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT). Houghton has a strong focus on the art of the book and publishing, and we try to find accurate terms to describe the material in hand. This can be seen as a bias toward expertise; will someone searching a topic as a beginner find a specialist’s term? Possibly not, so we add more common description elsewhere in the record to satisfy a keyword search.

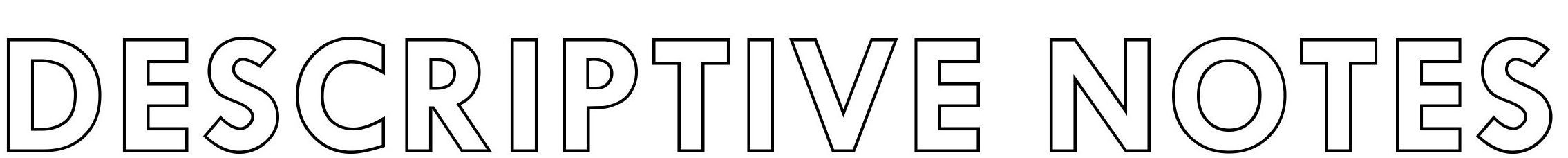

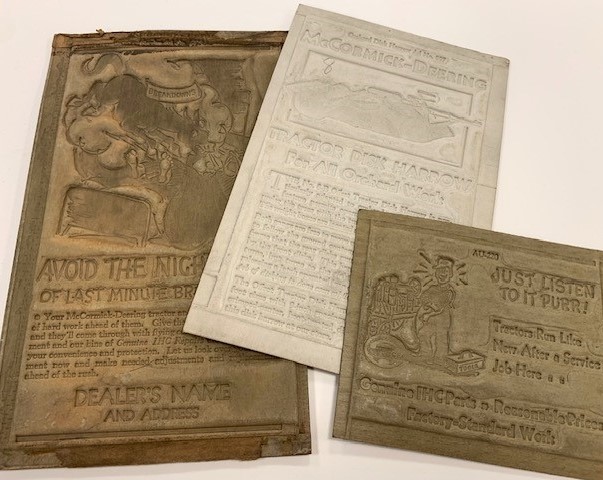

We recently acquired a collection now titled “Collection of newspaper and advertisement flongs.” There isn’t a better-known word for this specific product of the printing process, though it is sometimes described as a “papier-mâché mat” which I find odd…but which I included for the sake of keywords in a history note in the finding aid, along with the AAT definition. The title here serves to identify, and possibly to teach.

Contrary to the mandate of brevity, titles may be, justifiably, nearly as long as the tiny collections they describe:

- Process blocks commissioned by Philip and Frances Hofer for a Christmas keepsake,

- Drawings and related materials for Peter Kuper’s adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,

- Hester Pickman watercolors and letters to David Biddle concerning a trip to Pakistan, India, and Japan,

- Collection of photographs and printed ephemera relating to roller skater Jessie Darling

In these four cases, the omission of any of the key terms could leave a wrong impression. In the Jessie Darling example, it could boil down to “Collection related to Jessie Darling.” That would send the researcher deeper into the record to figure out who Jessie Darling was and why we acquired the collection, but would their curiosity last that long? Sometimes the sparkle in the curator’s eye should be spelled out first, hence the added descriptor “roller skater.” (For the record, ChatGPT 3.5 preferred the title “Rolling Stardust: A Chronicle of Jessie Darling’s Spotlight on Skates”.)

Our role in the creation of archival description used to be opaque; in the interest of transparency and truth-telling, we reveal more about our process and especially about our biases and limitations. I feel the responsibility of this exposure but can’t afford to dwell on it. For good or for ill, titling has become automatic for me, and I try to practice it with a light heart. I accept that my successor will start right in and do an excellent job. In reflective moments, though… I can’t help seeing accession titling (and all of accessioning) as a specialized practice requiring years of experience. The art in it remains invisible.

I have not, so far, asked an AI instance for help in accession titling, with the one exception above. I have, however, asked what ChatGPT 3.5 would suggest as the main points of a blog entry on the art of archival accession titling. It was either ingratiating or remarkably in synch with my own thinking: “…a well-chosen title is not just a practical tool for discovery but can become an integral part of the collection’s legacy, shaping perceptions and influencing the way it is remembered and utilized by future generations.” Exactly!

Melanie Wisner is Accessioning Archivist for the Houghton Library, part of Archives, Arts, and Special Collections of the Harvard Library. She holds a certificate in Digital Information Management from the University of Arizona, an MSLIS from Simmons University and an AB in English from the University of California, Davis.