By Cathy Dorin-Black

Image above: Student processor Hailey Mandel [left] and library specialist Cathy Dorin-Black [right] discuss Hailey’s current project.

At the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) at NC State University Libraries, supervising archivists manage several graduate and undergraduate student employees who perform most of the department’s archival processing. Levels of description are divided between the student employees and supervising archivists—for example, a student employee rehouses and describes folders, while the supervising archivist provides the collection-level and MARC record description. Effective project management is crucial to ensure all steps of the workflow are accurately completed.

Currently, three full time staff archivists supervise ten undergraduate and six graduate students who do processing as at least part of their job. Needless to say, it takes a lot of coordination and organization on the part of supervisors to guarantee that these student employees have plenty to work on with the appropriate level of difficulty, and that they receive the amount of support they need. Staff must regularly check work to make sure processing is accurate. They must also have a reserve of projects ready to go for when students’ current projects are finished. They frequently finish sooner than we think!

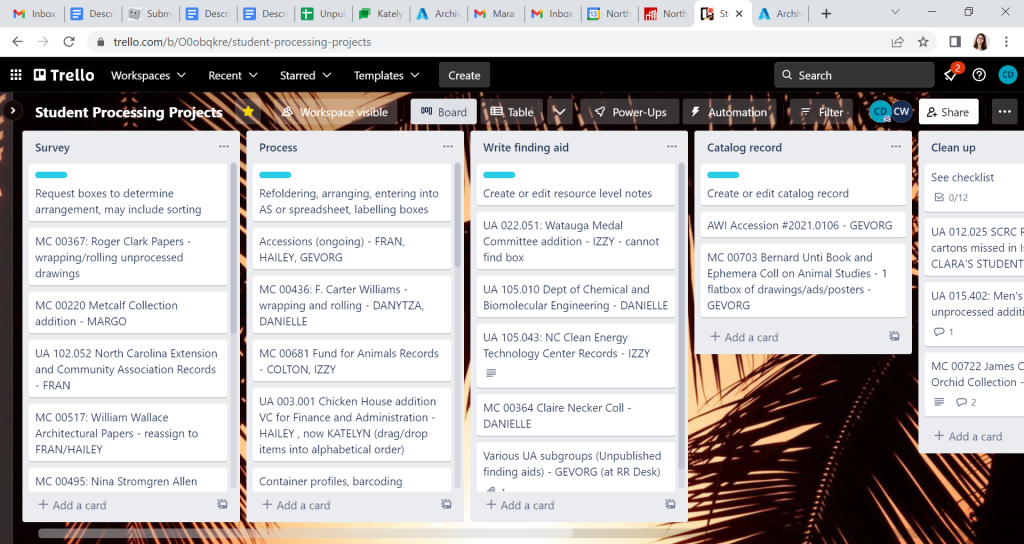

One way to manage these many moving parts is through the use of Trello, a project management tool in which cards are moved through columns representing steps of a workflow.

In this “Processing Projects” Trello board, each project is given a card and there are column headings for each step of the workflow. Steps include:

- Survey: This includes checking processing priorities for projects and surveying them for level of difficulty. It may also include setting up a workflow or arrangement scheme for less experienced processors to follow. Experienced processors or supervisors will complete this step.

- Process: This includes refoldering, re-boxing, and entering metadata into ArchivesSpace or a spreadsheet. Any processor can complete this step.

- Write finding aid: This includes creating or editing the resource level notes. Typically a supervisor or more experienced processor will complete this step. It is, however, helpful to receive feedback from the processor about topics covered so that the Scope and Contents note and subject headings can be constructed. Often processors maintain a Google Doc with this information.

- Catalog record: This includes creating or editing the MARC record in OCLC and importing into our ILS. Supervisors and more experienced processors will complete this step.

It’s important to note that different roles are involved with different steps in the process. For example, if the processor is an experienced graduate student, they may be able to proceed with columns 3 and 4, writing the finding aid and catalog record. However, if they are a less experienced processor, a supervisor may jump in when the card is advanced to the “Write finding aid” column and finish up the following steps. Regarding who is trained on steps 3 and 4 (“Catalog record”), supervisors will consider if the student is working with us long enough to justify the training and practice required, as well as if they are considering a career in archives where this training would be beneficial for their future goals.

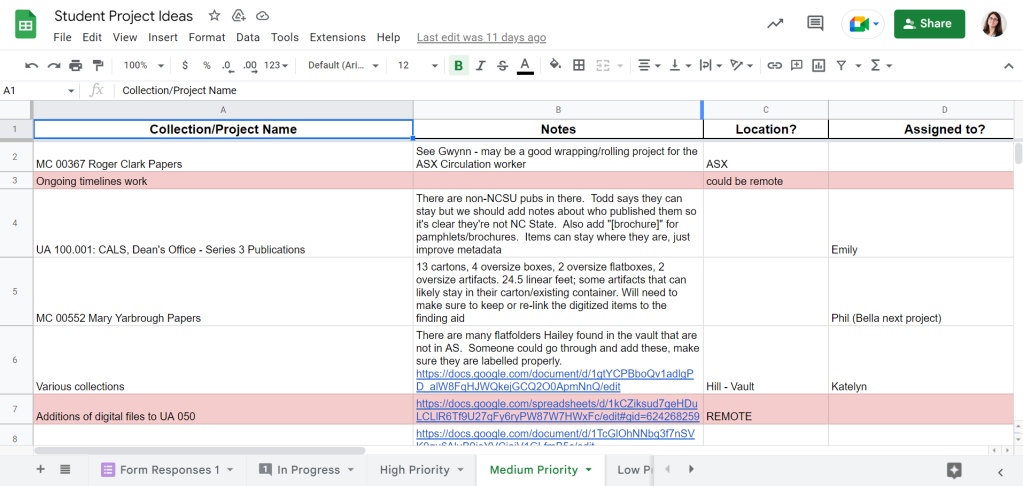

A Google Sheet of potential processing projects, maintained by supervising archivists and contributed to by curators, keeps the “Survey” column up to date.

The sheet has different tabs for level of priority and notes are usually made about the level of expertise needed, as well as a tab populated by a Google Form, which is completed whenever a processing project begins. Therefore, the sheet also tracks all projects in process.

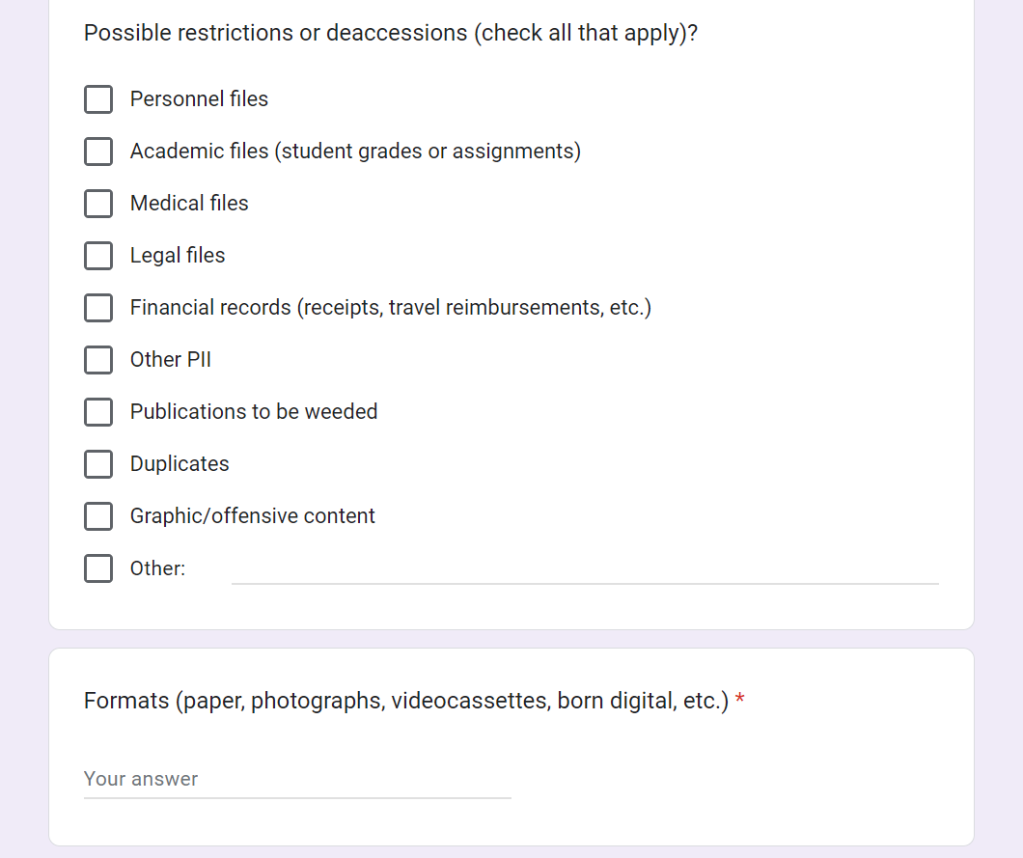

The form asks, among other things, what possible restrictions or deaccessions there may be, what formats there are, what types of containers are needed for housing, and what preservation concerns could come up. Either the processor or the supervising archivist fills out this form, giving us valuable information on what supplies may need to be ordered. It also tracks linear feet and the date a project began—good data for end of year reporting.

Weekly group meetings (sometimes via Zoom, sometimes in person) are scheduled for supervising archivists to look over the student project spreadsheet and determine who needs a new project and what might be appropriate. We consider what is high priority for the curators, where the collection will be processed (we have two locations), if it can be transported easily, what the level of difficulty is, and whether it is amenable to group processing or better for an individual project. Any questions supervising archivists may have about arrangement, preservation, or the specifics of processing can be addressed in these meetings as well. Sometimes it is very helpful to talk through a topic and find that another processor has encountered the same situation in the past.

We also have a once a month meeting that includes everyone (experienced or not) who processes or manages processing in the department. One purpose of these meetings is to share challenges encountered in processing: How do we house this unusual artifact? How should we arrange this particular collection? Should this scrapbook be taken apart or kept together? It’s beneficial to answer these questions with all processors present, in case they come across a similar situation in their work. We also disseminate information about technology, physical processing space, and departmental policy updates, so that all processors stay on the same page. Additionally, it is engaging for processors (especially those new to the profession) to hear about the various collections people are working on. Many times the processors meetings feature guest speakers (for example, the Preservation Librarian periodically makes presentations on identifying mold or the Digital Archivist talks about born digital workflow) or discussion topics (recent ones include emotional labor in the archives, reparative archival description, and processing born digital materials). This may introduce students and some supervisors to topics they may not have encountered yet. With students always coming onboard, it is helpful to rotate and repeat topics periodically.

Finally, while online tools and group meetings are key parts of project management, some things are best addressed in one-on-one meetings in person. Any number of strange situations can come up during processing, and sometimes it is best to examine up close and individually. At the SCRC, supervising archivists make regular rotations through our student employees to meet with them at their workstations. Some students do not always feel comfortable approaching their supervisor and will be more inclined to ask important questions during these check-ins. Supervisors can also clearly communicate any problems they have noticed while checking their work.

Project management can get overwhelming when there are lots of employees and not many supervisors to manage them. Competing processing priorities, student employee schedules, levels of expertise, and turnover can complicate things, but having the right tools in place can help keep projects on track. Thanks to these project management tools and techniques, the SCRC has been able to maintain a consistent amount of production, resulting in ever-evolving resources for our researchers to discover.

Cathy Dorin-Black is a library specialist at the Special Collections Research Center at NC State University Libraries. She manages archival processing in the department.