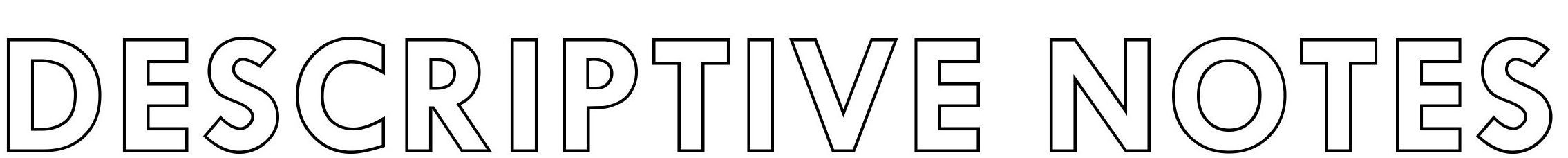

*Image above taken from the dealer-provided description for the Collection of toys and ephemera depicting Black life held at the Eberly Family Special Collections Library

By Mae Casey

The collection development policy at the Eberly Family Special Collections Library at Penn State University is a living document, frequently revisited and revised to ensure our collections are growing in strategic directions. Over the past two years, curators have been purchasing collections from dealers; often these collections relate to underrepresented groups and are ideal for instruction. The collections are split between ones that were created by a single person or group, such as the Pittsburgh Improvement League records, or ones that are a baseline of collection items that will be added to over time. One such collection is the Menstruation and gynecological health ephemera collection, which was initially purchased in 2021 from a single dealer and contained 27 items. The first accession record notes, “This is an artificial collection and periodic additions are expected as it is being actively archived,” and since that time over twenty items have been purchased and added to the collection. Because these collections and accruals generally come to us with dealer descriptions and inventories, they require a different approach to description. They provide us the opportunity to give patrons more than the typical minimal level of description, but there are some strings attached. They create additional steps in the accessioning process because the dealer’s “sales language” needs to be stripped away to reveal concrete information that must then be verified.

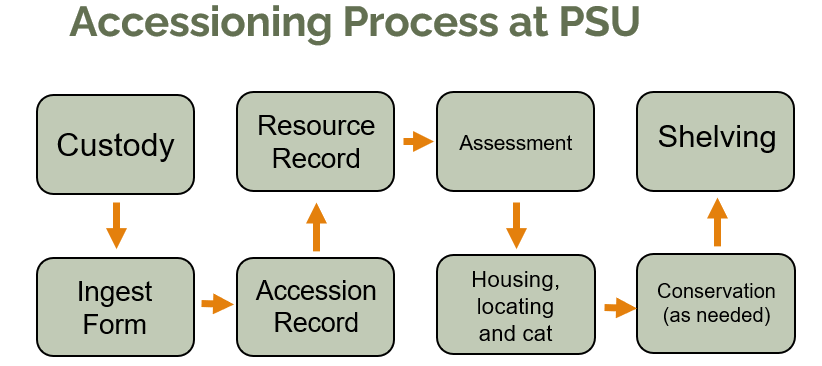

The Accessioning Workflow

Our accessioning process starts with curators completing and submitting an ingest form along with important documents such as deeds of gift, invoices, inventories, and the like. These ingest forms are the foundation for the accession record which is, in turn, the foundation for new resource records, our term for finding aids. All public-facing descriptions are rooted in these ingest records. Our standard accessioning workflow also includes a step for minimal processing at the point of accessioning. There are practical reasons for this, the most relevant being that not every collection we take in will be earmarked to be fully processed. We simply don’t have the capacity to do that so, for many collections, the minimal processing we provide at accessioning is the full extent. The other reason is that we currently have no processing archivist on staff and have been told that this position is going to be unfilled for an indefinite period. Performing minimal processing at the point of accessioning results in more developed finding aids for patrons to use, providing access more quickly.

From an accessioning standpoint, purchased collections have certain benefits. The dealer often includes more detailed descriptions with historical or biographical information as well as inventories. These kinds of documents help me, the accessioning archivist, create more in-depth records at a quicker pace. This is a major benefit, especially given that these collections are generally acquired expressly for specific instruction or research requests, so it is important that the minimal finding aid is generated as efficiently as possible. The downside is that reviewing the documentation for necessary information creates extra work that is unique to purchases; I often need to perform additional steps to verify information, so that generalized or inaccurate “selling points” do not appear in our records. Successfully and efficiently describing purchased, artificial collections means achieving a balance between using information from vendors while staying true to the minimal accessioning workflow and generating sensitive, high quality finding aids.

Peeling Back the Layers

When reviewing the descriptive information provided by dealers, it’s important I always keep a dealer’s purpose top of mind: their goal is to sell collections and the accompanying descriptions are often overly complimentary of the collection. That said, nearly every dealer description has objective information that can be truly useful in describing a collection or its components; there is a process to dig out that from under the flowery, sales language it is buried in. When I’m reviewing documentation, there are questions that I always ask. What information is fact-based? For individuals accessing the finding aid, which details would help them determine if a collection or item is what they are looking for? What information should be used in finding aid notes to communicate context? How should the creator’s language be incorporated into the notes?

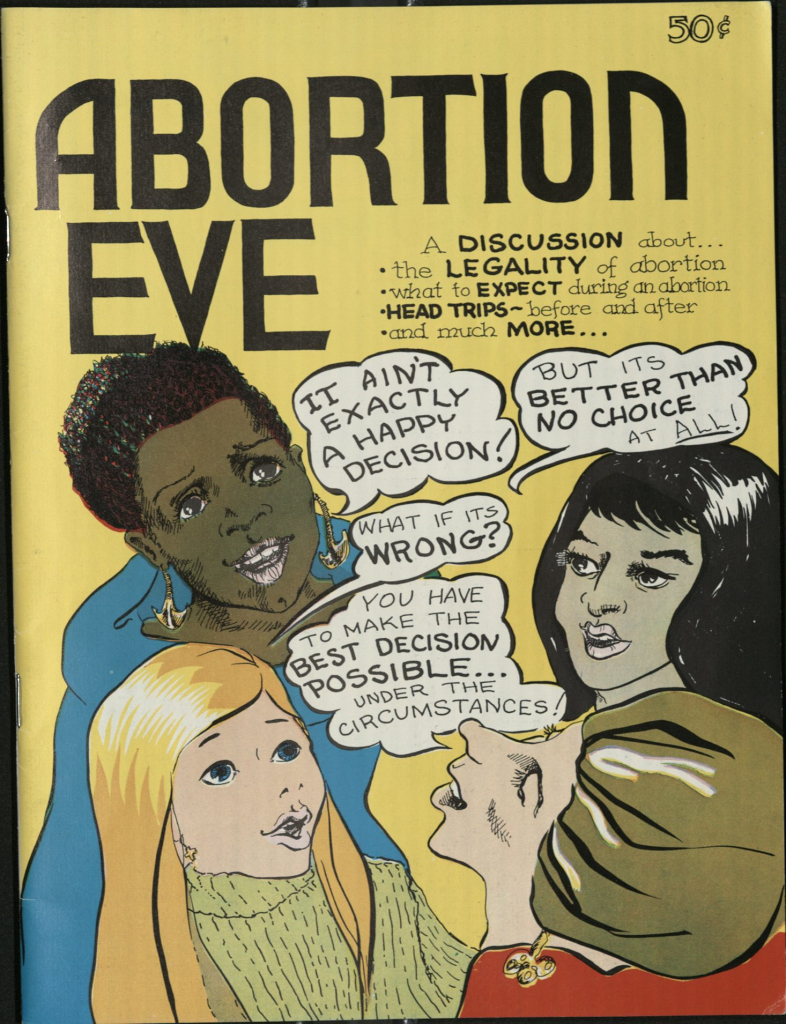

Feminist Publications

For example, we have the Feminist publications collection which includes several comic books created by women in the 1970s during the women’s liberation movement. The collection’s various contents “discuss feminist issues such as sex work, domestic violence, and incarceration; and reprints of legal and sociological reports, articles, and opinion pieces from the 1970s and 1980s.” As a person who has no prior knowledge of political comics or underground comic movements, I was relieved that the dealer sent brief descriptions of the items. That said, the language was effusive and polarizing, focused on communicating the message of the comic as opposed to simply describing it. There was helpful information, I just had to dig for it.

The dealer description is on top and the description used in the finding aid is the one below [2]. Emotional words and political opinion are embedded in that original description. I wanted to understand the comic and its greater purpose within the women’s liberation movement. When writing the scope and content note for this item, I reviewed and highlighted text that is objective and would be useful for a patron. I also took extra time to speed read through the comic itself so I could include summary information about the comic’s plot and to do some superficial research on the creator and the movement. Finally, I paraphrased the creator’s words directly from the cover in an effort to ensure their voice and intent was more fully communicated. The resulting note aggregates information about the historical context of the comic; a summary of its plot; and a general list of the larger topics discussed in the comic. While not perfect, this more streamlined description provides a complete and balanced explanation of the object that would help a patron determine if this is an item they would want to request and review.

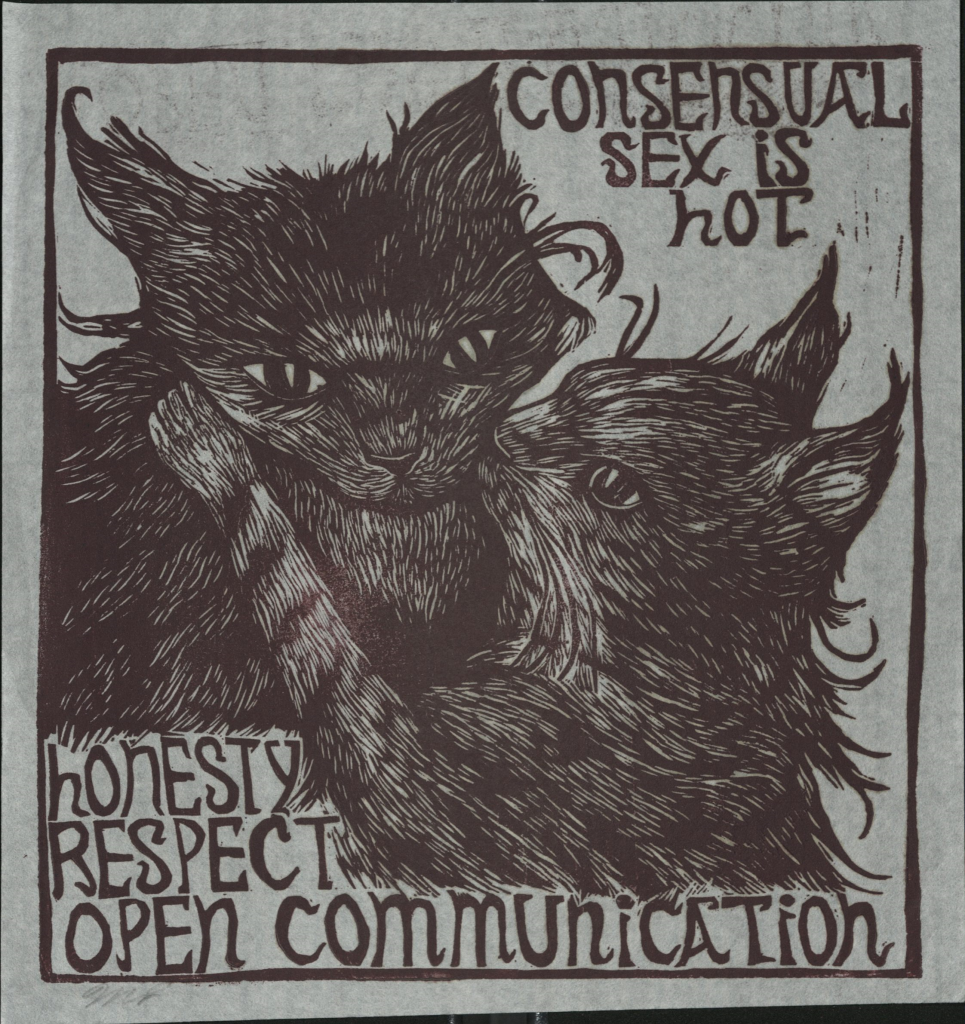

Meredith Stern’s I Can’t Believe I Still Have to Protest this Fucking Shit: 20 Years of Reproductive Justice Artwork collection

In the next example, the dealer is also the artist who created the individual items over the course of her career before gathering them into the curated collection that we purchased. Meredith Stern titled her collection I Can’t Believe I Still Have to Protest this Fucking Shit: 20 Years of Reproductive Justice Artwork and wrote a description of each piece of art. The individual descriptions generally included the artwork’s title, dimensions, materials, date of creation, and some description which, at times, veered more into Stern’s personal philosophy and values. I was challenged because the collection offered the rare opportunity to incorporate the creator’s voice – usually, our collections are received posthumously – and sharing that information with researchers could provide a unique depth to the finding aid. The question, again, was how do I create balance?

Again, the provided description is on the top and the one used in the finding aid is on the bottom [3]. Truthfully, there was precious little information (yellow highlight) about the actual piece in this descriptive blurb. Most of it is devoted to Stern’s explanation of her beliefs surrounding the importance of using sex education to support consensual sex. The description makes it clear this is a topic she is passionate about, and it would provide a researcher who could not see the artwork, only the finding aid, an understanding of the piece’s message. The flip side is that it doesn’t actually describe the physical image. In this instance, I chose to plainly describe the image while contextualizing it within a general statement about Stern’s beliefs. Again, not perfect, but it’s more streamlined than the original and is based in factual description while still incorporating the creator’s voice.

Conclusion

My refinement of this workflow is still very much in process, but my biggest take away at this point is that, while these dealer descriptions save me time and effort in certain areas, they require work in others. In a traditional gifted or transferred collection, I’d be responsible for creating all notes, summaries, and descriptions, and that is a time investment. Working with purchased and/or artificial collections, I have descriptions and inventories, but they require fact-checking, historical research, and contextualizing. Regardless of the descriptive path, my goal with all accessions is to complete minimally processed records that support our patrons’ search for knowledge. Keeping that goal top of mind helps me to work through our processes with flexibility and common sense.

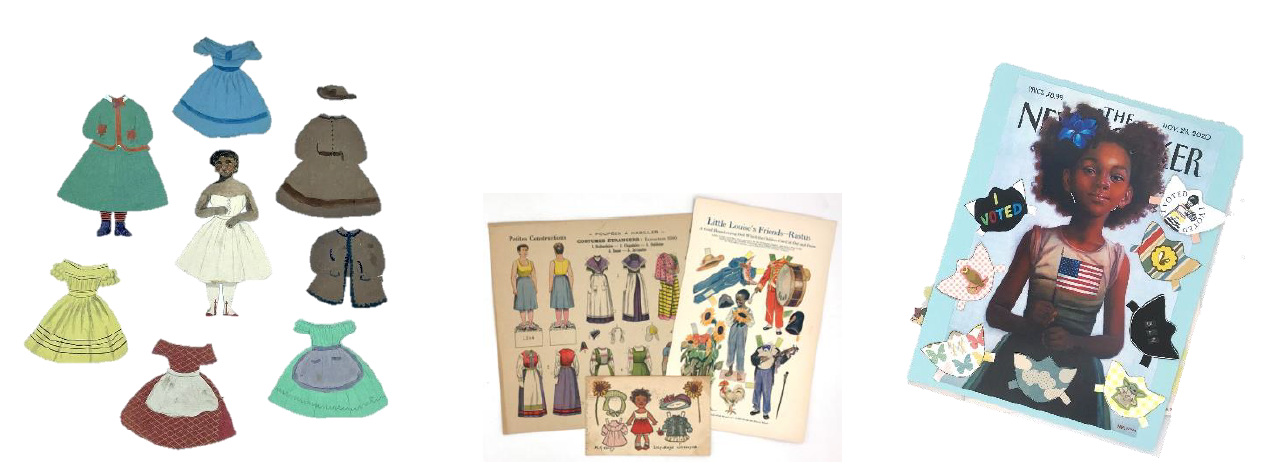

[1] These descriptions were taken directly from dealer-provided descriptions focused solely on selling the collections. “The First LGBTQ Business Association in the USA: Records of the Tavern Guild of San Francisco” from the dealer Carpe Librum; “The Progression in the Perception of Black Identity Late 19th-Century through 2020” from the dealer Tolland; and “ARCHIVE OF A DISTINGUISHED AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMAN EDUCATOR WHO WAS ACTIVE IN PITTSBURGH AND LIVED TO 106” from the dealer James E. Arsenault & Company.

[2] The quoted information is taken from the dealer description “FIVE FEMINIST COMICS” by seller Camp Books.

[3] The quoted information is taken from the artist Meredith Stern’s original description of her work; she provided these descriptions in a document titled “‘I Can’t Believe I Still Have To Protest This Fucking Shit.’ 20 Years of Reproductive Justice Artwork Created by Meredith Stern.”

Mae Casey is the Accessioning and Collections Management Archivist at the Penn State Eberly Family Special Collections Library. She previously presented on her experiences in accessioning at the SAA 2023 Records Meeting in the session “Ethical Accessioning for Access in a post-Pandemic Environment” and virtually at the Society of Southwest Archivists 2023 Annual Meeting in the session “Creating More Inclusive Minimal Description: Implementing Inclusive Practices at Accessioning.“